ABSTRACTS

Where the Sediments Are

John K. Reed, Michael J. Oard, Peter Klevberg

Confidence in forensic natural history increases when data are simple, observable, and complete. Larger scale often helps. For continental sedimentary rock and marine sediments, the best combination of these factors would be found in assessing their global volume and distribution. Geologists developed estimates long ago, but only in recent decades have database and mapping technology combined to allow reasonably accurate global maps of continental and marine sediment. Just recently, a good estimate of the volume and average thickness of the ocean sediments became available through the GlobSed project. The volume and thickness of the continental sediments is more difficult to describe for several reasons; defining the continent-ocean boundary is one. Defining Precambrian sedimentary basins and their relationship to the Genesis Flood adds uncertainty, but the goal of defining the global distribution of Flood sediments is worth pursuing.

Where the Sediments Are

John K. Reed, Michael J. Oard, Peter Klevberg

Abstract

Confidence in forensic natural history increases when data are simple, observable, and complete. Larger scale often helps. For continental sedimentary rock and marine sediments, the best combination of these factors would be found in assessing their global volume and distribution. Geologists developed estimates long ago, but only in recent decades have database and mapping technology combined to allow reasonably accurate global maps of continental and marine sediment. Just recently, a good estimate of the volume and average thickness of the ocean sediments became available through the GlobSed project. The volume and thickness of the continental sediments is more difficult to describe for several reasons; defining the continent-ocean boundary is one. Defining Precambrian sedimentary basins and their relationship to the Genesis Flood adds uncertainty, but the goal of defining the global distribution of Flood sediments is worth pursuing.

Keywords: sediment distribution, marine sediments, sedimentary rock, GlobSed, Macrostrat, erosion, deposition, Flood

Introduction

A feature of uniformitarian history is an insistence that its interpretation of the past is science-i.e., "historical science" (c.f., Cleland, 2013). Ultimately, this claim is diminished because incomplete data, ad hoc hypotheses, and the depths of time multiply into a weight of uncertainty that science cannot bear. That is why we have always preferred the mixed question paradigm (Adler, 1965) that acknowledges inherent uncertainties absent a threat to core ideas (Reed and Klevberg, 2015).

Ideas and technologies change, but the fundamental question of natural history is "what can we know about Earth's past?," followed closely by "how do we know?" Modern geohistory offers inconsistencies even at the level of the definition of its fundamental principle of uniformitarianism (Gould, 1965, 1975; Reed, 1998; 2010; 2011; 2018; Miall, 2015;). Another problem is the lack of completeness of observed phenomena (e.g., erosion volume, landscapes, strata, faulting) (Reed and Klevberg, 2017, 2018).

A related issue is scale. Only recently have a plethora of observations, database handling, and computer-aided mapping begun to clarify the nature of large-scale phenomena. For sedimentary rock (strata), the most basic, large-scale features are the volume and distribution of sediment bodies and sedimentary basins on a global scale. A related phenomenon is the depth to basement. For diluvialists, assessing which portions of these strata are diluvial is critical to understanding their work.

If a global flood shaped the face of the Earth, its fingerprints should be visible in these phenomena. With respect to absolute volume, Reed and Oard (2017) demonstrated that it is uniformitarian time, not diluvialism, that has problems-contrary to the hackneyed assertion that there are too many rocks to have been generated in a one-year Flood. The real problem is exactly the opposite-that there are not enough rocks for uniformitarian processes acting over deep time. Issues like this force numerous ad hoc excuses, such as erosion or nondeposition.

But volume and average thickness are only part of the story. The distribution of sediments and sedimentary rocks conveys more helpful information. Based on the principle that the youngest features will be the least obscure (at least in outcrops though not necessarily in oil wells), we focus on the accumulations of sediment in the oceans from the GlobSed project, especially the thick continental margin sediments. Complementary smaller-scale data, such as the composition and interior architecture of these sediment bodies; the lateral, vertical, and stratigraphic arrangement of fossils; and the relationship between sediments and mechanisms of erosion, transport, and deposition are subjects for later study.

Historical Background

It was only in the last century that geologists could empirically begin assessing global sedimentary volume and distribution. Blatt (1970, p. 259) noted, "All published estimates of sedimentary volumes are based on reasonable assumptions but inadequate data." Early estimates were based on proxies, such as rock and ocean geochemistry (e.g., Clarke, 1924), though it proved a poor proxy (Peters et al., 2018). Recent decades have seen an explosion in advanced mapping, data processing, and marine seismic data that has allowed more accurate maps of global sediment distribution.

But even those early efforts pointed to major issues, the most basic being the significantly inequitable distribution between continents and oceans, and then, in marine settings, between continental margins and deep ocean basins. While definitions between these regimes can vary by researcher and whether they employ geographic vs. geologic criteria, for the purposes of this paper, we follow the boundary definitions of Straume et al. (2019) in which the continental and marine sediment boundary is the shoreline. An in-depth analysis of this issue is too complex to pursue here, but is acknowledged.

Harvey Blatt

Blatt's (1970) estimate of global sediment volume and mean thickness was extrapolated from geologic maps of North America. He defined continental margin sediments by their underlying basement (sialic vs. oceanic) and included those over sialic crust, thus including some continental margin sediments, in his calculation. He estimated the mean thickness for the continents at 1,829 m. Deep marine sediments, estimated from limited data at the time, returned a mean thickness of 244 m. His total global mean thickness was 820 m, close to Clarke's (1924) 762 m, derived geochemically from comparing sodium in the ocean to that in rocks.

Blatt and Jones (1975) went further, estimating the areal extent of various lithologies exposed at Earth's surface by a coarse random sampling technique and statistical checks. Of 3,000 random points on the globe, 768 were usable as data points. Based on those, they concluded that sedimentary rocks were exposed on 66% of the globe, give or take 3.5%. They also noted variations in igneous rocks between continents, based on centers of Cenozoic volcanism (see their Table 1). Estimating percentages of volume by age, they predicted a declining curve of volume-to-age based on erosion and recycling over millions of years: "All workers have agreed that the relationship between sedimentary rock age and its outcrop area is described by a decay curve like that for radioactive minerals" (Blatt and Jones, 1975, p. 1088).

Alexander Borisovich Ronov

Born in 1913, the Russian scientist Ronov spent his career at the Vernadski Institute of Geochemistry of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, studying crustal sedimentation and geochemistry. That work was summarized in English in a monograph published by the American Geological Institute in 1983, reprinted from the International Geology Review (1982), which was translated from a Russian monograph published in 1980. Sadly, the 1983 monograph is difficult to find outside of university libraries. It compactly, yet comprehensively, discussed sediment distribution, thickness, chemistry, and stratigraphy.

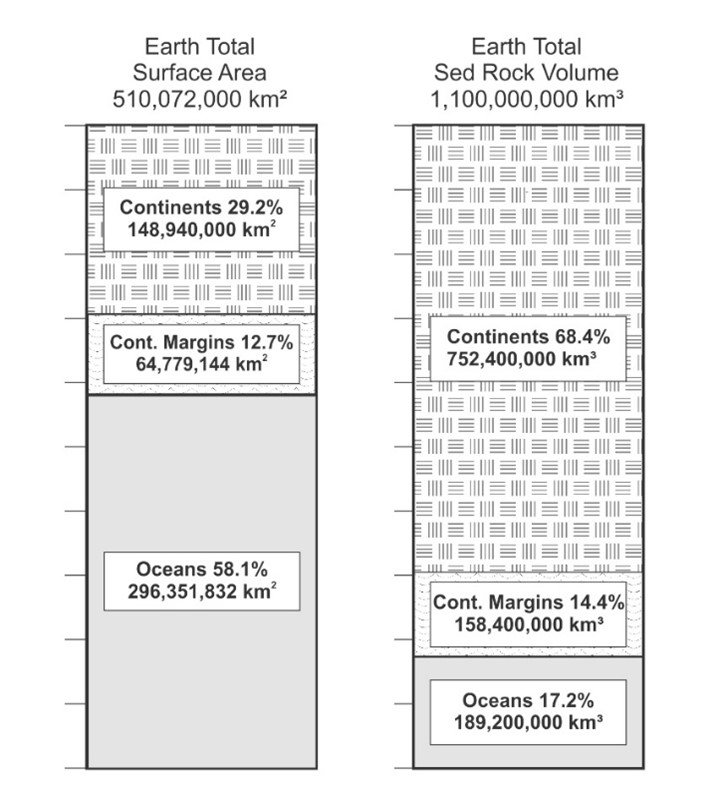

Ronov (1983) also noted the obvious discrepancy between marine and terrestrial sedimentation (Figure 1) and estimated an average global thickness of 2,200 m-based on a continental average of 5,000 m, a deep ocean figure of 400 m, and a continental margin thickness of 2,500 m. His total volume for sedimentary rock (including most of the Precambrian sedimentary rocks) was 1.1 billion km3 or 11% of the crust. Ronov used the term "stratisphere" for the outer crust, composed of layered sedimentary and volcanic rocks above crystalline basement. Of Earth's land area, nearly 149 million km2, the stratisphere covers 119 million km2 (46,004,844 mi.2), or 80%. The remaining 20% is the exposed crystalline basement of the shields. Blatt and Jones (1975) had estimated that sedimentary rocks covered only 66% of land area. Part of the difference is Blatt and Jones (1975) including part of the continental margins, but part was simply the data deficiencies of that time and the greater data density studied by Ronov.

Ronov (1983) also evaluated rock composition, noting that Proterozoic rocks were largely terrigenous, with 11% carbonate, 8% volcanics, and virtually no "evaporites." (Because of numerous uniformitarian problems explaining the origin of huge salt and gypsum deposits, we do not believe they originated from evaporating seawater, but are instead precipitates. We will use the researcher's terminology with quote marks.) In contrast, he calculated the Phanerozoic as 59% terrigenous, 23% carbonate, 16% volcanics, and having three times more "evaporites" than found in Precambrian rocks. Since Ronov's work is over 50 years old, more "evaporites" have been found in the Precambrian in Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and India. Ronov noted that geochemical mass balance estimates for the mass and types of sedimentary rocks do not agree with actual data and suggested changing ocean chemistry through time.

Blatt and Ronov represent the apex of the pre-computer-world understanding of global sediment distribution. Their works were solidly empirical yet suffered from a lack of data and deepwater drilling activity, particularly limiting their understanding of the marine sediments, as well as the challenges of analyzing and mapping massive data sets. Given the absence of today's computational technology, Ronov's (1983) work, especially, is impressive for its systematic, quantitative approach. However, their studies are now a half century out of date.

Figure 1. Contrast between surface area of sediment platforms (left) and volume of sediments (right), based on Ronov's (1983) calculations.

Modern Estimates of Global Sediments

Refinement in our understanding of global sediment distribution has been attempted since the 20th century. Better estimates of continental sediments have been made, spearheaded by efforts like the Macrostrat project (Peters, 2006), although their assessments of other continents do not match the data-driven analysis of Clarey (2020). Oceanic sediment distributions are much more thorough and accurate, thanks to the truly global picture provided by the GlobSed project (Divins, 2003; Whittaker et al., 2013; Straume et al., 2019).

GlobSed

We will summarize the important volume and distribution of sediments from the GlobSed project. A rough estimate for the total sediment thickness for the oceans was published by Divins (2003), as version 1 of GlobSed. In version 2, a better estimate of the sediment thickness in the Australian and Antarctic regions and the area in between was added by Whittaker et al. (2013). The first two attempts contained uncertainties that were addressed by Straume et al. (2019). Earlier uncertainties included the lack of adequate thicknesses where sediments were greater than 1.5 km and poorly resolved areas due to a lack of seismic data. Version 3 of GlobSed (Straume et al., 2019) increased the projected volume of oceanic sediments by an astounding 29.7% over earlier versions. New data for the northeast Atlantic, Mediterranean Sea, and the Arctic and Antarctic continental margins were largely responsible for this change.

Straume et al (2019) calculated about 3.37 x 108 km3 of sediment over an oceanic area of about 3.63 x 108 km 2 for an average thickness of 927 m. He divided up the oceans into three areas: (1) the continental margins, (2) the deep sea, and (3) the area between the margins and the deep sea (Table I). The continental margins represent 12.9% of the ocean area, 0.469 x 108 km2, with a sediment volume of 1.43 x 108 km 3 and an average sediment thickness of 3,044 m. The deep-sea area is defined as starting 200 km oceanward of subsurface continent/ocean boundary, which represents 76.9% of the oceanic area or 2.79 x 10 8 km2. The sediment volume in the deep sea is 1.13 x 108 km3 with an average thickness of 404 m. The area between the margin and the deep sea is 0.37 x 108 km2 , about 10.2% of the ocean area. It has a sediment volume of 0.81 x 10 8 km3 with an average thickness of 2,189 m.

Table I. The three divisions of the ocean according to Straume et al. (2019): (1) the continental margins, (2) the area between the margins and the deep ocean, and (3) the deep ocean. The area of the deep ocean is defined as the area 200 km oceanward of the subsurface continent/ocean boundary.

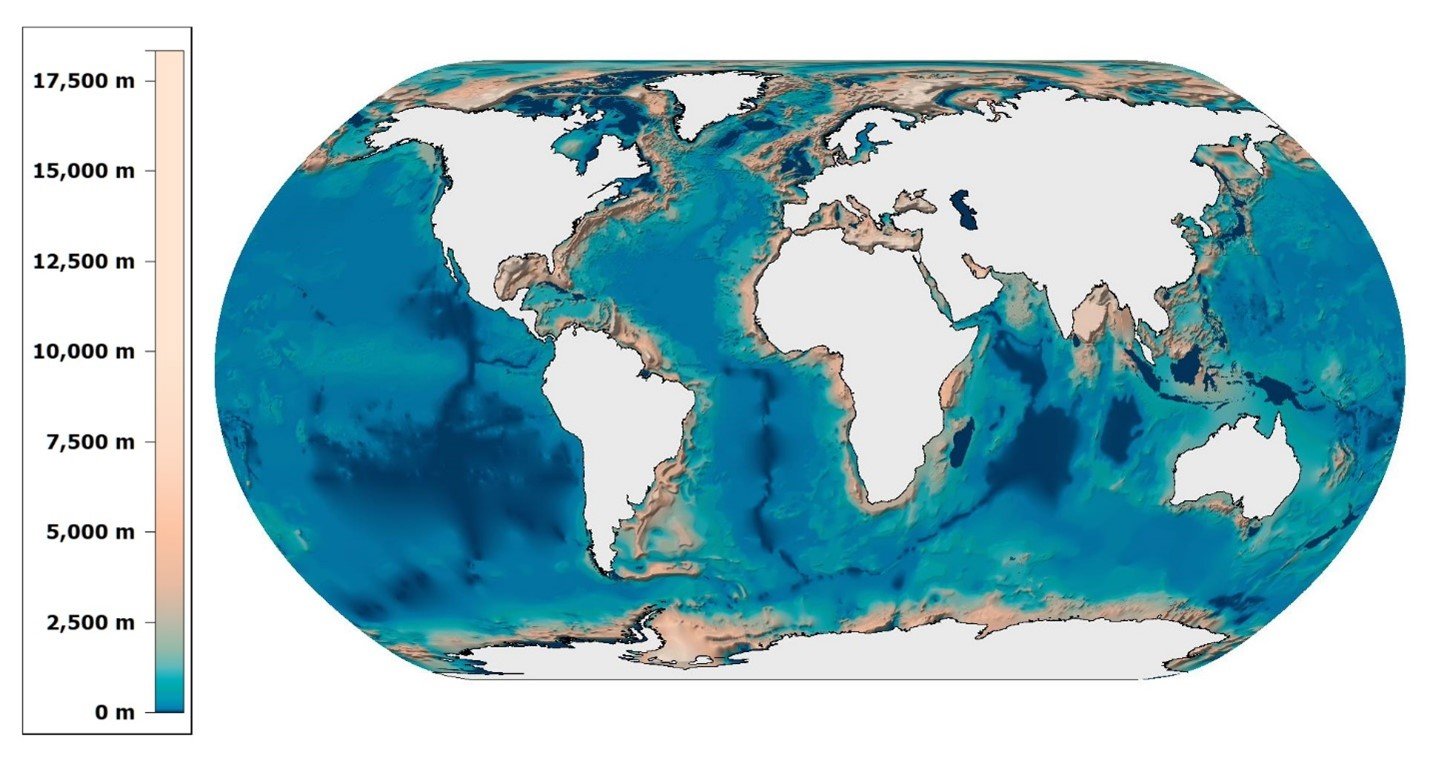

The thickest marine sediments (Figure 2) are along the Arctic and Antarctic continental margins, the Gulf of Mexico, the eastern United States, the Bay of Bengal, and the Mediterranean Sea.

Figure 2. Most recent GlobSed map of distribution of marine sediments. Modified from Straume et al. (2019).

Macrostrat

Macrostrat is a research project that collects geological data that characterize the lithology, age, and physical-chemical properties of rocks and sediments of the Earth's upper crust (Peters et al., 2018). It is built on the COSUNA (Correlation Of Stratigraphic Units of North America) charts (Peters, 2006). The COSUNA charts were produced by the American Association of Petroleum Geologists in the 1980s and resulted in hundreds of local to regional generalized geological columns, using well and any other data available at the time (Childs, 1985). COSUNA charts show numerous unconformities and missing time because of the emphasis on the age of the strata, based mainly on fossils (Miall, 2016). Based on Macrostrat data, Peters and Husson (2017) calculated an average depth of continental Phanerozoic sediments of 3,630 m. If Ronov's (1983) estimate (980 m) for continental Precambrian strata is added, they reach a total of 4,610 m. They based this result on North America and the circum-Caribbean region, and extrapolated to the rest of the continental areas, which is a grave weakness in their procedure. They used a little continental margin sediment and the oceanic area around the Caribbean islands. Their estimate is very close to Ronov's (1983) estimate, which was of greater global reach but lower resolution.

Tim Clarey and Davis Werner

Clarey and Werner (2017, 2018) and Clarey (2019, 2020) are assessing continental sediment thickness using megasequences based on Sloss's (1963) work. He started with the COSUNA data, which he heavily edited, and then gathered his own data across North America, South America, Africa and the Middle East and Europe (Clarey, 2019, 2020) and most recently totals from Asia (unpublished). His data set was compiled from oil wells, measured sections, and selected seismic data. Many of his data points are from wells on the continental margins that were drilled in the last few decades. He concludes that there is about an average thickness of 3,280 m of sediment for the Phanerozoic across the continents and the continental margins combined (personal communication, 2022). If Ronov's Precambrian total of 980 m average is correct (Clarey believes it to be much less), the average sediment thickness on the continents, including new data from Asia, is 4,260 m. Clarey and Werner also compiled a separate average thickness for just the continental margins across the same five continents, finding an average thickness of 3,820 m on the margins. This is considerably thicker than on the land portion of the continents (personal communication of unpublished data by Clarey and Werner). This value is also higher than the average from GlobSed, and the difference may be because GlobSed included all the continents and because of different definitions of the continental margin.

We believe Clarey and Werner's estimate is more accurate but still needs to include Australia and Antarctica. We still need to find the average volume and thickness of the continental sedimentary rocks without the continental margin in order to compare with GlobSed. Their work and ours are still in progress. Clarey and Werner are now compiling stratigraphic columns across Australia (personal communication, 2022). Each megasequence is defined for its area on each continent, then an average thickness calculated for that area.

Contrary Conclusions for Predicted Volume of Strata with Age on the Continents

Sedimentary rocks are most commonly binned by age in both the Phanerozoic and Precambrian. This is the essence of every geologic map, the COSUNA charts, megasequences, and Macrostrat. However, as Reed and Oard (2017) noted, substantive uniformitarian predictions are often not confirmed in the field. This leads to numerous ad hoc justifications, narrative shifts, and polite silences.

It had been predicted that because of steadily-increasing time for erosion or due to a lack of deposition, the amount of strata on the continent should decrease exponentially back in time. This is a straightforward prediction of uniformitarian geology:

Exponential decrease in surviving quantity with increasing age is a basic prediction of any model in which sediments, once deposited, are subjected to a continuous random probability of destruction. (Peters and Husson, 2017, p. 323)

This makes logical sense, given the proposition of deep time, and, if anything, the effect is understated by uniformitarians relative to observed rates (c.f., Figure 7, Reed and Oard, 2017). Many researchers have advocated such an exponential decrease the older the age. For example, Blatt and Jones (1975, p. 1088) confidently asserted that, "All workers have agreed that the relationship between sedimentary rock age and its outcrop area is described by a decay curve like that for radioactive minerals."

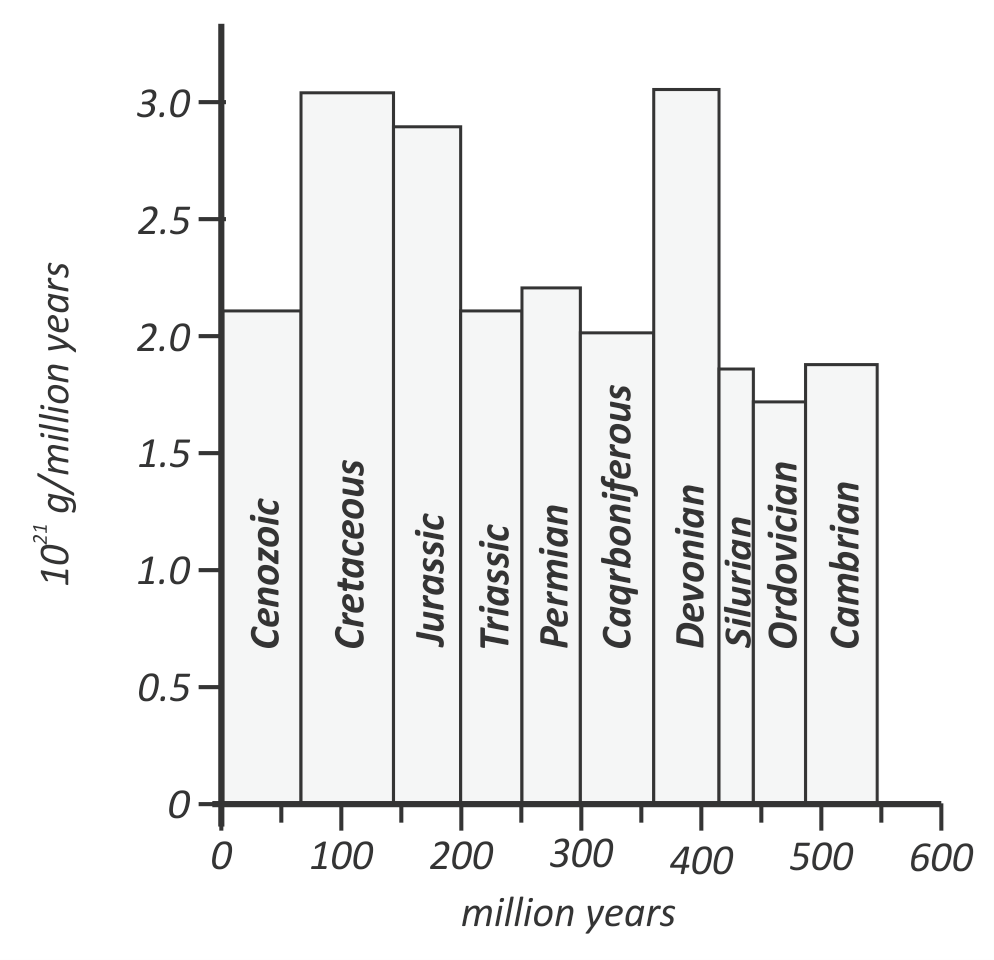

However, Ronov (1983) and Ronov et al. (1980) discovered that the field distribution of sediments by age ran counter to this accepted wisdom, noting that there was not a smooth exponential decrease of sediment volume with older age in the Phanerozoic (Figure 3). Ronov (1983, p. 12) was aware that this ran counter to both uniformitarian prediction and received wisdom:

The scale of the loss may be judged solely by statistics, assuming that the older the sedimentary rocks, the greater the likelihood that they have been eroded. In that case, the relative mass of the sedimentary rocks should gradually decrease from younger to older. Gregor… recently came to that conclusion, followed by Garrels and Mackenzie…. They established that the relative mass of sedimentary rocks should decrease according to an exponential law, from the present to the distant past.

However, field evidence (Figure 3) showed Ronov (1983, pp. 13-14, emphasis added) something else:

I constructed histograms… in which are plotted the relative masses of the sedimentary rocks assigned to each period of the Phanerozoic…. Contrary to expectation, the graphs do not reveal a regular decrease in the relative masses of rocks with increasing time; instead, they show period fluctuations. Thus, I must maintain firmly that globally significant erosion of masses of sedimentary rocks did not take place during the course of the Phanerozoic time, and that the fluctuations were most probably controlled by periodic changes in the intensity of sedimentation. It must be acknowledged… that over the larger time intervals… equal to entire eras… the relative mass of sedimentary rocks tends to decrease…. The decrease is weak in the Phanerozoic interval, but much sharper in the late Proterozoic interval.

Figure 3. Ronov (1983) compared total sediment mass by stratigraphic periods, showing that there was not a smooth exponential decline in sedimentation, as predicted by many, over time. Instead, mass varied indiscriminately. Contrast with Blatt and Jones' (1975) assertion of exponential decline in quote above. Modified from Ronov (1983, Figure 7).

The Macrostrat project, limited in scope because of its analysis of North America and the Caribbean, reinforced Ronov's (1983) conclusion that field data do not show an exponential decrease in sediment volume the older the age for the Phanerozoic:

Here we use comprehensive surface and subsurface data in North America as well as regional and global geological maps to show that decreasing sedimentary rock quantity with increasing age is not a prevalent pattern in the sedimentary rock record. (Peters and Husson, 2017, p. 323)

If the Precambrian sedimentary rock is included, there is of course a sharp decline of preserved volume from the Quaternary to the Mesoproterozoic, about 1,600 million years ago, but the main decline is from the Cambrian to the late Neoproterozoic, with little change throughout the Phanerozoic or older than the late Neoproterozoic.

However, Clarey and Werner (2017) and Johnson and Clarey (2021) have drawn opposite conclusions and shown that the volume of sedimentary rocks does decrease significantly back across the uniformitarian timescale. They argue this pattern is real because it was a progressive Flood, starting with minimal coverage early, followed by more and more coverage as the Flood year progressed (Clarey and Werner, 2017; Johnson and Clarey, 2021). At this point, we simply report the different results, which points out the difficulty of not only estimating the volume of strata on the continents but its pattern and age. We hope to address this issue in later papers.

Discussion

The amount of sediments on the continents and in the oceans is immense. The estimates of the volumes and average thickness will add clarity to the mechanisms for the generation of those sediments. Twentieth-century studies provided coarse estimates of the volume and thickness of sediments and sedimentary rocks (Blatt, 1970; Blatt and Jones; 1975; Ronov, 1983). Newer, more sophisticated projects show some differences and significantly more clarity for marine sediments because of the GlobSed project (Straume et al., 2019). However, the estimated volume and thickness of strata on the continents varies between researchers, partly because of Macrostrat using only North America and the Caribbean and the variable inputs of marine margin sediments and Precambrian sedimentary rocks. Researchers have obtained opposite conclusions on the widely believed exponential decrease in sediments with age that has been predicted by early uniformitarian scientists.

In a companion paper we will show that the distribution of ocean sediments does not fit well with uniformitarian inferences but is predicted by the Recessive Stage of the Flood (c.f., Schmich, 1980; Walker, 1994). Moreover, continental features, such as large planation surfaces, reinforce the massive erosion of the top of the sediments on the continents (Oard, 2008, 2013, 2014). Insights based on large-scale erosion and deposition during that stage can, in turn, cast light on the earlier processes and stages (Oard and Reed, 2017).

References

Adler, M.J. 1965. The Conditions of Philosophy. Atheneum Press, New York, NY.

Blatt, H. 1970. Determination of mean sediment thickness in the crust: A sedimentologic method. Geological Society of America Bulletin 81(1):255-262.

Blatt, H., and R.L. Jones. 1975. Proportions of exposed igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks. Geological Society of America Bulletin 86(8):1085-1088.

Childs, O.E. 1985. Correlation of stratigraphic units of North America: COSUNA. American Association of Petroleum Geologists 69(2):173-180.

Clarke, F.W. 1924. Data of geochemistry. U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 770, Washington, D.C.

Clarey, T. 2020. Carved in Stone: Geological Evidence of the Worldwide Flood. Institute for Creation Research, Dallas, TX.

Clarey, T.L., and Werner, D.L. 2017. The sedimentary record demonstrates minimal flooding during the Sauk deposition. Answers Research Journal 10:271-283.

Clarey, T.L., and Werner, D.L. 2018. Use of sedimentary megasequences to re-create pre-Flood geography. In Whitmore J.H. (editor), Proceedings of the Eight International Conference on Creationism, pp. 351-372. Creation Science Fellowship, Pittsburgh, PA.

Clarey, T. 2019. European stratigraphy supports a global Flood. Acts & Facts, November 27.

Cleland, C.E. 2013. Common cause explanation and the search for the "smoking gun." In Baker, V.R. (editor). Rethinking the Fabric of Geology. Geological Society of America Special Paper 502, pp. 1-10. Geological Society of America, Boulder, CO.

Divins, D.L. 2003. Total Sediment Thickness of the World's Oceans and Marginal Seas. NOAA (National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration). National Geophysical Data Center, Boulder, CO.; https://ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/sedthick/sedthick.html .

Gould, S.J. 1965. Is uniformitarianism necessary? American Journal of Science 263(3):223-228.

Gould, S.J. 1975. Catastrophes and steady-state Earth. Natural History 84(2):15-18.

Johnson, J.J.S., and T.L. Clarey. 2021. God floods Earth, yet preserves Ark-borne humans and animals: Exegetical and geological notes on Genesis, Chapter 7. Creation Research Society Quarterly 47(2):248-262.

Miall, A.D. 2015. A new uniformitarianism: Stratigraphy as just a set of "frozen accidents." In Smith, D.G., R.J. Bailey, P.M. Burgess, and A.J. Frasier (editors). Strata and Time: Probing the Gaps in our Understanding, Special Publication 404. Geological Society, London, UK, pp. 11-36.

Miall, A.D. 2016. The valuation of unconformities. Earth-Science Reviews 163:22-71.

Oard, M.J. 2008. Flood by Design: Receding Water Shapes the Earth's Surface. Master Books, Green Forest, AR.

Oard, M.J. (ebook). 2013. Earth's Surface Shaped by Genesis Flood Runoff. http://Michael.oards.net/GenesisFloodRunoff.htm .

Oard, M.J. (ebook). 2014. The Flood/Post-Flood Boundary Is in the Late Cenozoic with Little Post-Flood Catastrophism . http://michael.oards.net/PostFloodBoundary.htm .

Oard, M.J., and J.K. Reed. 2017. How Noah's Flood Shaped Our Earth. Creation Book Publishers, Powder Springs, GA.

Peters, S.E. 2006. Macrostratigraphy of North America. Journal of Geology 114(4):391-412.

Peters, S.E., and J.M. Husson. 2017. Sediment cycling on continental and oceanic crust. Geology 45(4):323-326.

Peters, S.E., J.M. Husson, and J. Czaplewski. 2018. Macrostrat: A platform for geological data integration and deep-time Earth crust research. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 19:1393-1409.

Reed, J.K. 1998. Demythologizing uniformitarian history . Creation Research Society Quarterly 35(3):157-165.

Reed, J.K. 2010. Untangling Uniformitarianism, Level I: A Quest for Clarity. Answers Research Journal 3:37-59.

Reed, J.K. 2011. Untangling Uniformitarianism, Level II: Actualism in Crisis. Answers Research Journal 4:203-215

Reed, J.K. 2018. Changing paradigms in stratigraphy-another new uniformitarianism? Journal of Creation 32(3):64-73.

Reed, J.K., and P. Klevberg. 2015. Battlegrounds of Natural History, Part III: Historicism. Creation Research Society Quarterly 51(4):177-185.

Reed, J.K., and P. Klevberg. 2017. Carol Cleland's defense of historical science, Part I: Deflating experimental science. Journal of Creation 31(2):103-109.

Reed, J.K., and P. Klevberg. 2018. Carol Cleland's defense of historical science, Part II: Rebuilding historical science. Journal of Creation 32(1):84-91.

Reed, J.K., and M.J. Oard. 2017. Not enough rocks: The sedimentary record and Earth's past. Journal of Creation 31(2):84-93.

Ronov, A.B. 1983. The Earth's Sedimentary Shell. American Geological Institute Reprint Series 5, Falls Church, Virginia.

Ronov, A.B., V.E. Khain, A.N. Balukhovsky, and K.B. Seslavinsky. 1980. Quantitative analysis of Phanerozoic sedimentation. Sedimentary Geology 25:311-425.

Schmich, J.E. 1980. Continental tilt. Creation Research Society Quarterly 17(2):114-117.

Sloss, L.L. 1963. Sequences in the cratonic interior of North America. GSA Bulletin 74(2):93-114.

Straume, E.O., C. Gaina, S. Medvedev, K. Hochmuth, K. Gohl, J.M. Whittaker, R. Abdul Fattah, J.C. Doornenbal, and J.R. Hopper. 2019. Globsed: Updated total sediment thickness in the world's oceans. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 10.1029/2018GC00815:1756-1772.

Walker, T. 1994. A Biblical geological model. In Walsh, R.E. (editor). Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Creationism, technical symposium sessions, pp. 581-592. Creation Science Fellowship, Pittsburgh, PA; biblicalgeology.net/.

Whittaker, J., A. Goncharov, S. Williams, R. Dietmar Müller, and G. Leitchenkov. 2013. Global sediment thickness dataset updated for the Australian-Antarctic Southern Ocean. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. doi: 10.1002/ggge.20181 .